IL GESTO

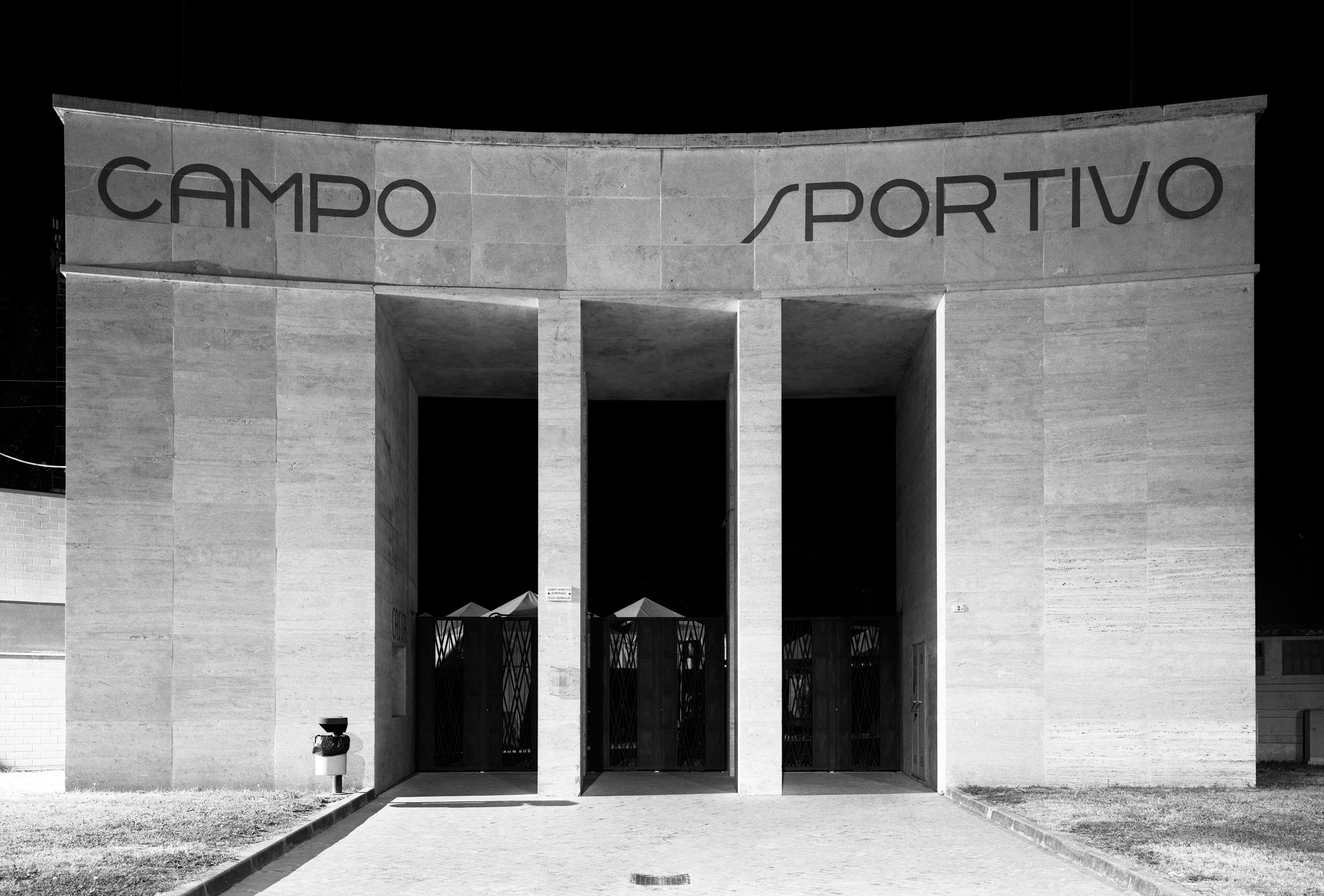

Italy 1922-1944New towns in the Italy of Mussolini

↓

Sous Mussolini, plus de 150 villes nouvelles sont construites sur la péninsule italienne et ses îles, dans le but de repeupler les campagnes, de coloniser le marais récemment asséchés et de développer les zones minières nécessaires à une économie autosuffisante.

Loin de la rhétorique monumentale des centres urbains,l’architecture de ces villages a été confiée à un groupe d’architectes talentueux, souvent d’origine juive, qui adhéraient à l’utopie d’une architecture combinant esthétique et fonctionnalité, vouée à la transmission de valeurs éthiques et communautaires.

Ce mouvement, qui s’étend des années 1920 aux années 1930, a donné naissance au mouvement RATIONALISTE italien. Cependant, l’adoption des lois raciales en 1936 et l’alliance avec l’Allemagne ont mis fin à cette expérience.

Les villes issues de ce projet ont connu des sorts variés : certaines sont tombées en ruines, tandis que d’autres sont devenues des centres prospères protégés par l’UNESCO.

Loin de la rhétorique monumentale des centres urbains,l’architecture de ces villages a été confiée à un groupe d’architectes talentueux, souvent d’origine juive, qui adhéraient à l’utopie d’une architecture combinant esthétique et fonctionnalité, vouée à la transmission de valeurs éthiques et communautaires.

Ce mouvement, qui s’étend des années 1920 aux années 1930, a donné naissance au mouvement RATIONALISTE italien. Cependant, l’adoption des lois raciales en 1936 et l’alliance avec l’Allemagne ont mis fin à cette expérience.

Les villes issues de ce projet ont connu des sorts variés : certaines sont tombées en ruines, tandis que d’autres sont devenues des centres prospères protégés par l’UNESCO.

Under Mussolini, more than 150 new towns were built on the Italian peninsula and its islands, with the aim of repopulating the countryside, colonising and develop the mining areas needed for a self-sufficient economy.

Far from the monumental rhetoric of urban centres, the architecture of these villages was entrusted to a group of talented architects, often of Jewish origin, who embraced the utopia of an architecture combining aesthetics and functionality, dedicated to the transmission of ethical and community values.

This movement, which lasted from the 1920s to the 1930s, gave rise to the Italian RATIONALIST movement. However, the adoption of racial laws in 1936 and the alliance with Germany put an end to this experiment.

The towns that grew out of this project have had varying fates: some have fallen into ruin, while others have become prosperous centres protected by UNESCO.

Far from the monumental rhetoric of urban centres, the architecture of these villages was entrusted to a group of talented architects, often of Jewish origin, who embraced the utopia of an architecture combining aesthetics and functionality, dedicated to the transmission of ethical and community values.

This movement, which lasted from the 1920s to the 1930s, gave rise to the Italian RATIONALIST movement. However, the adoption of racial laws in 1936 and the alliance with Germany put an end to this experiment.

The towns that grew out of this project have had varying fates: some have fallen into ruin, while others have become prosperous centres protected by UNESCO.

PARIS:

PANORAMA DU DEVELOPPEMENT URBAIN↓

Le Panorama de Paris ici présenté décrit une étendue bien plus importante qu’un simple tour de périphérique.

Tout en s’inscrivant, pour sa rigueur formelle, dans le sillage de l’école documentaire italienne de Basilico et Niedmayer, Luca Nicolao trace ici un voyage temporel dans la capitale qui n’est pas sans rappeler le fameux vers de Baudelaire : « la forme d'une ville change plus vite, hélas ! que le coeur d'un mortel »1.

Plus que d’une géographie de la ville, nous y verrions donc plutôt une description archéologique de son présent, ainsi qu’une image de son avenir. Or, l’habilité du photographe est de minimiser cette étendue temporelle dans un flux presque imperceptible, si semblable à notre attention inégale, passive et dispersive.

Nous commençons en quelque sorte par un passé proche, avec les barres d’immeubles en bordure du périphérique des années ‘50 - constructions désavouées que l’extension de Paris voudrait détruire, transformer, oublier. On ressent beaucoup d’intimité dans le regard de Nicolao envers ces seuils de la ville et les vies qui y circulent. « C’est un bruit de fond, une perception distraite, une expérience esthétique instable, anesthésiante. C’est la bande visuelle de nos existences » dit-il en arpenteur de l’urbain, oeil qui se fond dans l’anonymat du paysage.

Nicolao guette la surprise pour mieux saisir l’ordinaire : des visages en chemin, un mouvement incessant, indifférent à la monumentalité qui l’entoure. Le champs contre champs transforme ici la valeur des échelles : de ces grilles verticales et monochromes on passe à l’expérience esthétique du passant, fait d’une horizontalité grouillante de bruits, odeurs, regards croisés, trajets ininterrompus.

Puis, par un glissement presque anodin, nous changeons de paradigme, les immeubles haussmanniens traçant la voie jusqu’au centre historique et son présent continuel, figé dans son spectacle qui se réitère jour après jour. Dans ces sites où le tourisme de masse a investi chaque parcelle de la ville l’ironie du photographe devient alors plus perceptible et la confusion entre reflet et réalité presque palpable. Concorde, Tuileries, Tour Eiffel…l’auteur se prend aussi à ce jeu autoréférentiel, sans pourtant jamais quitter sa rigueur documentaire, aussi impitoyable envers son sujet qu’envers nous qui le regardons avec incrédulité et émerveillement. Es ce bien cela Paris?

Encore plus que cela. Un arrêt de métro plus tard, et nous voilà dans son futur. Bâtis sur les ruines du passé, les nouveaux éco quartiers sont les paradigmes d’une réalité dessinée sur écran. Les gestes, les attitudes des gens répondent en tout point à ce programme visuel, comme si vraiment l’architecture pouvait à elle seule disposer de nos corps, les agencer ensemble, fonder une communauté à partir d’individus.

C’est sur sa fin que la série prend une allure presque philosophique, prophétique du sens que Walter Benjamin donnait à l’architecture, comme image présente des projections du demain, rêve ou cauchemar devenu matière et que seul l’oeil mécanique de la photographie est capable de restituer à nous les humains, les passants, les hommes et femmes distraits des villes contemporaines.

1 C. Baudelaire, « Le cygne » dans Les Fleurs du mal 1857

Paris, 30 Novembre 2018Camilla Bevilacqua

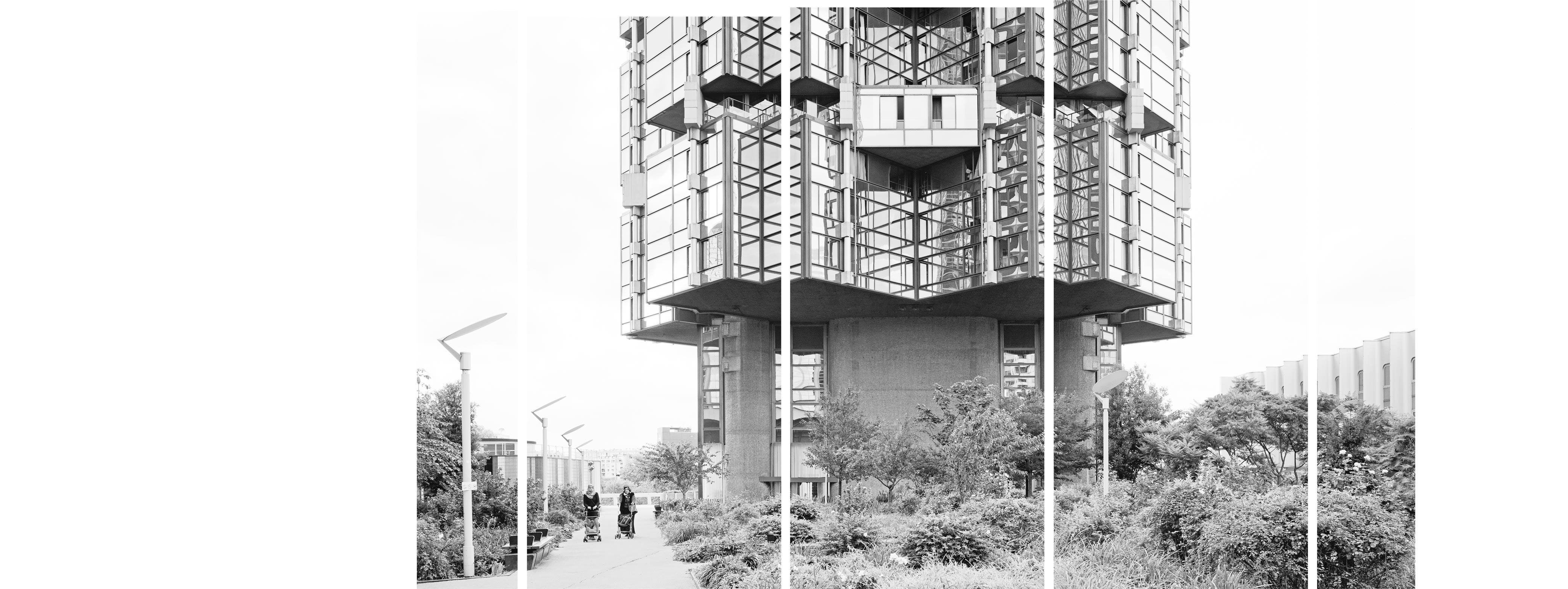

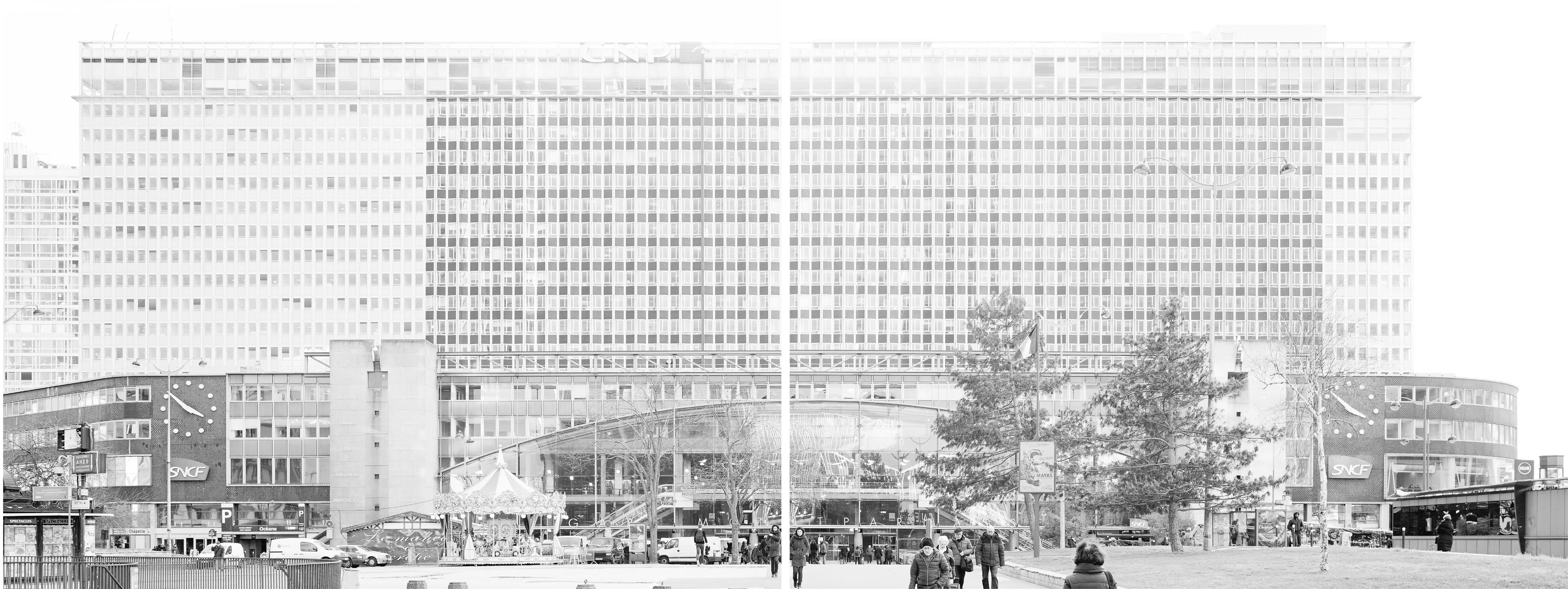

The Panorama of Paris presented here describes an area much larger than a simple tour of the ring road.

While following in the footsteps of the Italian documentary school of Basilico and Niedmayer in terms of formal rigour, Luca Nicolao traces a temporal journey through the capital that is reminiscent of Baudelaire's famous line: "the shape of a city changes more quickly, alas! than the heart of a mortal "1 .

Rather than a geography of the city, we would see in it an archaeological description of its present, as well as an image of its future. Yet the photographer's skill is to minimize this temporal expanse into an almost imperceptible flow, so similar to our uneven, passive and dispersive attention.

We begin, as it were, in the near past, with the building blocks on the edge of the ring road in the 1950s - disowned constructions that the expansion of Paris would like to destroy, transform, forget. There is a great deal of intimacy in Nicolao's view of these thresholds of the city and the lives that move through them. "It is a background noise, a distracted perception, an unstable, anaesthetic aesthetic experience. It is the visual strip of our existences," he says as a surveyor of the urban, an eye that melts into the anonymity of the landscape.

Nicolao watches for the surprise to better capture the ordinary: faces on the way, an incessant movement, indifferent to the monumentality that surrounds it. The field against field transforms here the value of scales: from these vertical and monochrome grids we pass to the aesthetic experience of the passer-by, made of a horizontality swarming with noises, smells, crossed glances, uninterrupted journeys.

Then, by an almost harmless shift, we change paradigm, the Haussmannian buildings tracing the path to the historic centre and its continuous present, frozen in its spectacle that repeats itself day after day. In these sites where mass tourism has taken over every part of the city, the photographer's irony becomes more perceptible and the confusion between reflection and reality almost palpable. Concorde, Tuileries, Eiffel Tower...the author also plays this self-referential game, without ever leaving his documentary rigour, as ruthless towards his subject as towards us who look at him with incredulity and wonder. Is this Paris?

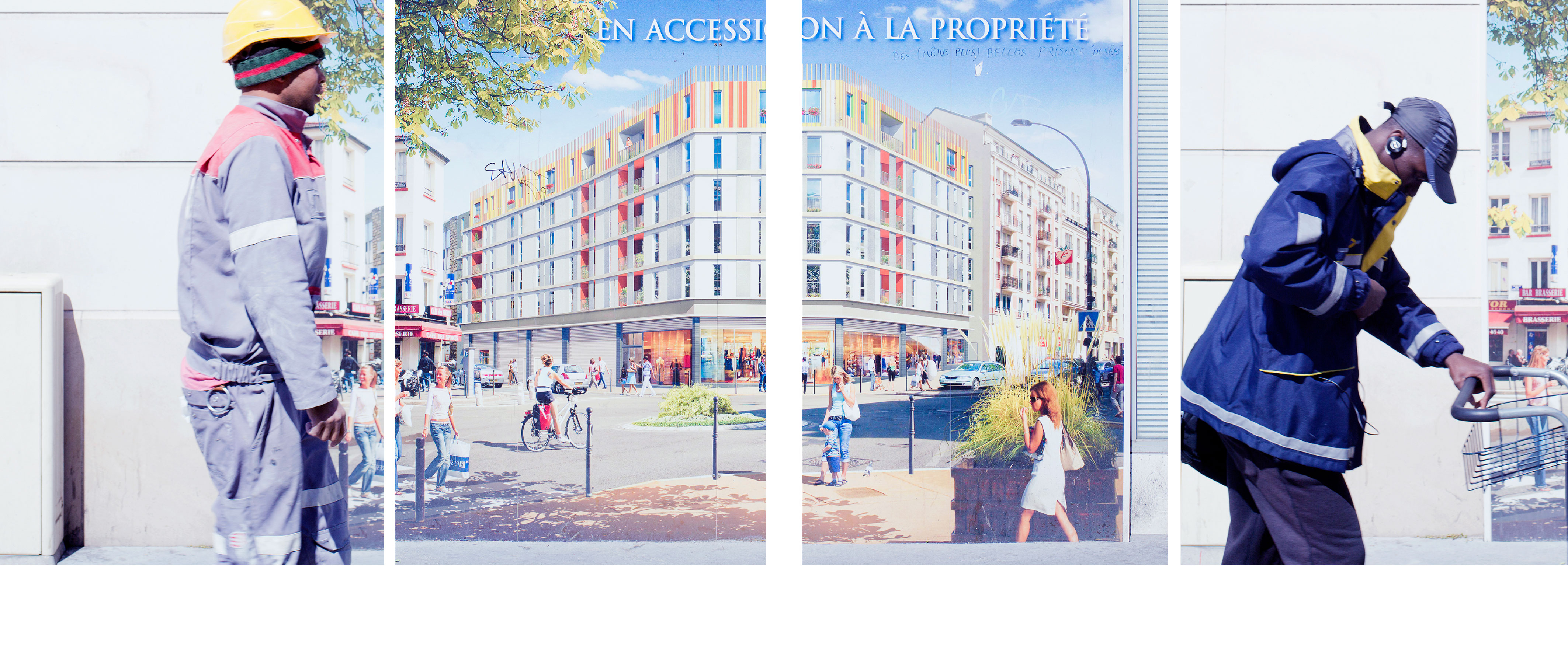

More than that. One metro stop later, and we are in its future. Built on the ruins of the past, the new eco-neighbourhoods are the paradigms of a reality drawn on screen. The gestures and attitudes of the people respond in every way to this visual programme, as if architecture alone could dispose of our bodies, arrange them together, found a community from individuals.

It is at the end that the series takes on an almost philosophical aspect, prophetic of the meaning that Walter Benjamin gave to architecture, as a present image of tomorrow's projections, a dream or nightmare that has become matter and that only the mechanical eye of photography is capable of restoring to us humans, the passers-by, the distracted men and women of contemporary cities.

1 C. Baudelaire, "The Swan" in Les Fleurs du mal 1857

Paris, 30 November 2018 Camilla Bevilacqua

THE RE-MIXED CITY

Grand Paris2014-2021

LUX LAND

Luxembourg2016-2018

︎︎︎

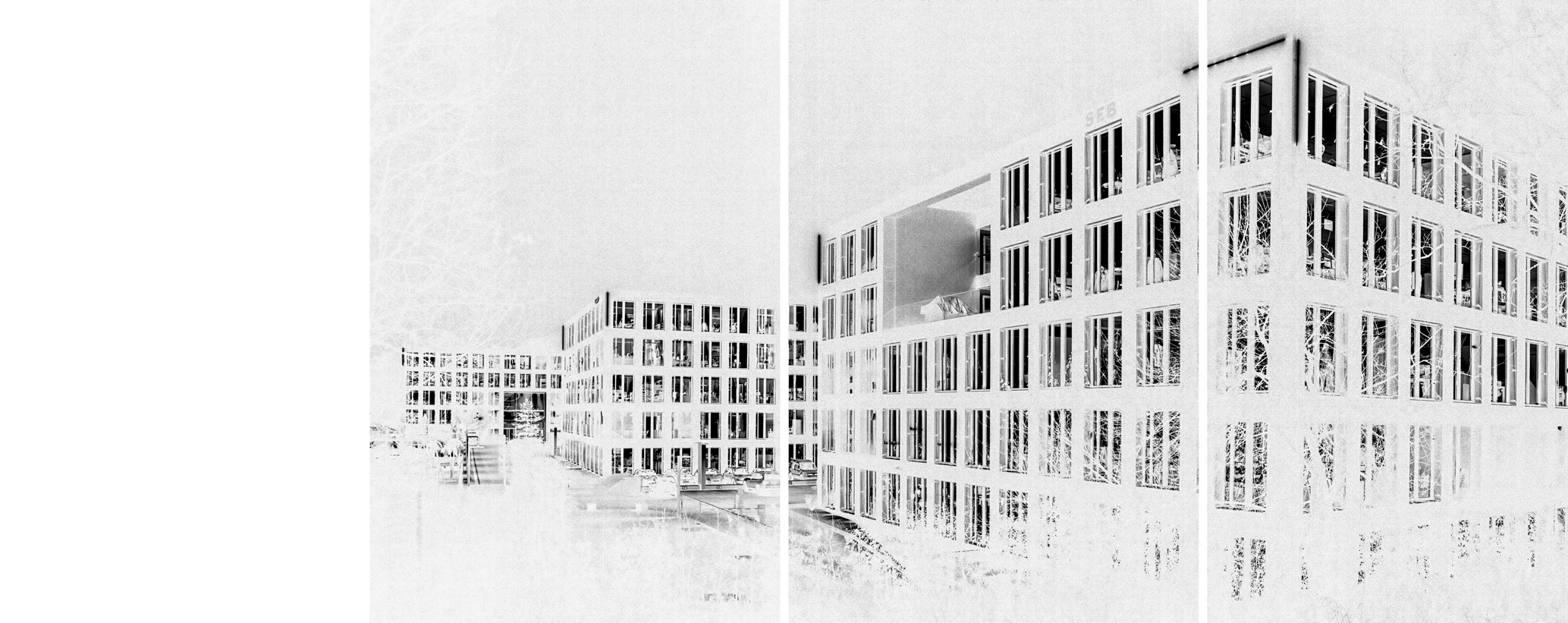

Lewis Baltz wrote some twenty years ago that Luxembourg, with its 70,000 inhabitants and 270 banks, reminded him of the "Las Vegas Strip", with banks instead of casinos.

This country has built its recent wealth by offering an advantageous tax system to the fortunes of the world, in accordance with the legislation of the European Union, of which it is a major political player.

The major groups of the global economy, banks, companies, financial engineering firms, rub shoulders with the institutions of the European community in the city and its surroundings.

This landscape punctuated by the innumerable grids of facades, imposing buildings, reflections and shimmers, constantly reiterates the enigma of contemporary power, where controllers and controlled merge into a single setting.

Kirchberg, Belval, La Cloche d'Or are the new cities of the 21st century. Built thanks to financial capital, designed by computer, controlled as a private corporate space, they reveal a growing strategy of occupation of public space by private and supranational actors.

This country has built its recent wealth by offering an advantageous tax system to the fortunes of the world, in accordance with the legislation of the European Union, of which it is a major political player.

The major groups of the global economy, banks, companies, financial engineering firms, rub shoulders with the institutions of the European community in the city and its surroundings.

This landscape punctuated by the innumerable grids of facades, imposing buildings, reflections and shimmers, constantly reiterates the enigma of contemporary power, where controllers and controlled merge into a single setting.

Kirchberg, Belval, La Cloche d'Or are the new cities of the 21st century. Built thanks to financial capital, designed by computer, controlled as a private corporate space, they reveal a growing strategy of occupation of public space by private and supranational actors.

Lewis Baltz ecrivait il y une vingtaine d'années, que le Luxembourg, avec ses 70 000 habitants et ses 270 banques, lui rappelait la "Las Vegas Strip", mais avec les banques à la place des casinos.

Ce pays a construit sa richesse récente en offrant une fiscalité avantageuse aux fortunes du monde, en accord avec la législation de l'Union Européenne dont elle est un acteur politique majeur.

Les grands groupes de l'économie globale, banques, entreprises, cabinets d'audit et conseil financier, côtoient les institutions de l'Union dans la ville et ses alentours.

Ce paysage rythmé par les innombrables grilles des façades, les imposants bâtiments, les reflets et les miroitements, réitère sans cesse l'énigme du pouvoir contemporain, où contrôleurs et controlés se fondent dans un seul décor.

Kirchberg, Belval, La Cloche d'Or sont les villes nouvelles du XXIème siècle. Construites grâce au capital financier, conçues par ordinateur, contrôlées comme un espace privé d'entreprise, elles révèlent une stratégie d'occupation grandissante de l'espace public de la part d'acteurs privés et supranationaux.

Ce pays a construit sa richesse récente en offrant une fiscalité avantageuse aux fortunes du monde, en accord avec la législation de l'Union Européenne dont elle est un acteur politique majeur.

Les grands groupes de l'économie globale, banques, entreprises, cabinets d'audit et conseil financier, côtoient les institutions de l'Union dans la ville et ses alentours.

Ce paysage rythmé par les innombrables grilles des façades, les imposants bâtiments, les reflets et les miroitements, réitère sans cesse l'énigme du pouvoir contemporain, où contrôleurs et controlés se fondent dans un seul décor.

Kirchberg, Belval, La Cloche d'Or sont les villes nouvelles du XXIème siècle. Construites grâce au capital financier, conçues par ordinateur, contrôlées comme un espace privé d'entreprise, elles révèlent une stratégie d'occupation grandissante de l'espace public de la part d'acteurs privés et supranationaux.

NAXOS

2013

Nàxos, Cyclades. Disséminées dans les collines, des étranges structures en béton ponctuent les paysages mythiques de l’île grecque. Il s’agit de maisons, lotissements, parfois d’immenses quartiers abandonnés en cours de construction. Nés de la frénésie inconsciente des marchés, symboles inédits d’une macroéconomie venue côtoyer les vestiges de la Grèce millénaire et de ses formes essentielles, ces temples vides accueillent désormais à l’ombre de leurs espaces géométriques des troupeaux des bergers et les chiens errants.

On y reconnaît les œuvres figées d’un pays qui ne sait toujours pas à quoi ressemblera son avenir, ni quand il pourra (se) construire à nouveau.

On s’étonne aussi de leur aspect minimaliste, si semblable aux cubes incomplets de l’artiste américain Sol Lewitt, qui concevait ses œuvres selon une logique combinatoire strictement mathématique. Ici, les lois complexes de l’économie globalisée ont généré des formes dans le paysage qui se présentent comme des œuvres de Land Art. C’est alors une ballade inédite qui commence à Nàxos, où des constructions laissées à l’état brut dialoguent avec les formes de l’architecture grecque, où les sites millénaires apparaissent à travers le contour d’un rectangle aux angles nets comme le portail d’un temple apollinien.

Une étrange impression s’installe, comme si ces architectures fantasques étaient là juste pour nous questionner sur les mystères du temps et de sa réversibilité. Car ces bâtiments de l’ère post-capitaliste aux allures d’œuvres contemporaines sont des chantiers, mais aussi des ruines. Moyen terme entre deux vecteurs temporels opposés, ils anticipent et commémorent en même temps, nous rappelant d’un avenir qui ne pourra véritablement advenir qu’aux termes d’une révolution dans le mode de lire ces paysages et de mesurer sur ceux-ci l’impact de facteurs extérieurs, imprévisibles et incontrôlables.

Camilla Bevilacqua

On y reconnaît les œuvres figées d’un pays qui ne sait toujours pas à quoi ressemblera son avenir, ni quand il pourra (se) construire à nouveau.

On s’étonne aussi de leur aspect minimaliste, si semblable aux cubes incomplets de l’artiste américain Sol Lewitt, qui concevait ses œuvres selon une logique combinatoire strictement mathématique. Ici, les lois complexes de l’économie globalisée ont généré des formes dans le paysage qui se présentent comme des œuvres de Land Art. C’est alors une ballade inédite qui commence à Nàxos, où des constructions laissées à l’état brut dialoguent avec les formes de l’architecture grecque, où les sites millénaires apparaissent à travers le contour d’un rectangle aux angles nets comme le portail d’un temple apollinien.

Une étrange impression s’installe, comme si ces architectures fantasques étaient là juste pour nous questionner sur les mystères du temps et de sa réversibilité. Car ces bâtiments de l’ère post-capitaliste aux allures d’œuvres contemporaines sont des chantiers, mais aussi des ruines. Moyen terme entre deux vecteurs temporels opposés, ils anticipent et commémorent en même temps, nous rappelant d’un avenir qui ne pourra véritablement advenir qu’aux termes d’une révolution dans le mode de lire ces paysages et de mesurer sur ceux-ci l’impact de facteurs extérieurs, imprévisibles et incontrôlables.

Camilla Bevilacqua

Nàxos, Cyclades. Scattered in the hills, strange concrete structures punctuate the mythical landscapes of the Greek island. They are houses, housing estates, sometimes huge abandoned districts under construction. Born from the unconscious frenzy of the markets, new symbols of a macroeconomy that has come to rub shoulders with the vestiges of the thousand-year-old Greece and its essential forms, these empty temples now welcome, in the shadow of their geometric spaces, flocks of shepherds and stray dogs.

One recognizes the frozen works of a country that still does not know what its future will look like, nor when it will be able to build itself again. One is also surprised by their minimalist aspect, so similar to the incomplete cubes of the American artist Sol Lewitt, who conceived his works according to a strictly mathematical combinatory logic.

Here, the complex laws of the globalized economy have generated forms in the landscape that are presented as works of Land Art.

It is then a new ballad that begins in Nàxos, where constructions left in their raw state dialogue with the forms of Greek architecture, where the thousand-year-old sites appear through the outline of a rectangle with sharp angles like the portal of an Apollonian temple.

A strange impression is then created, as if these whimsical architectures were there just to question us on the mysteries of time and its reversibility. For these buildings of the post-capitalist era with the appearance of contemporary works are

building sites, but also ruins

. Middle term between two opposite temporal vectors, they anticipate and commemorate at the same time, reminding us of a future that can only really happen in terms of a revolution in the way we read these landscapes and measure the impact of external, unpredictable and uncontrollable factors on them. unpredictable and uncontrollable.

Camilla Bevilacqua

One recognizes the frozen works of a country that still does not know what its future will look like, nor when it will be able to build itself again. One is also surprised by their minimalist aspect, so similar to the incomplete cubes of the American artist Sol Lewitt, who conceived his works according to a strictly mathematical combinatory logic.

Here, the complex laws of the globalized economy have generated forms in the landscape that are presented as works of Land Art.

It is then a new ballad that begins in Nàxos, where constructions left in their raw state dialogue with the forms of Greek architecture, where the thousand-year-old sites appear through the outline of a rectangle with sharp angles like the portal of an Apollonian temple.

A strange impression is then created, as if these whimsical architectures were there just to question us on the mysteries of time and its reversibility. For these buildings of the post-capitalist era with the appearance of contemporary works are

building sites, but also ruins

. Middle term between two opposite temporal vectors, they anticipate and commemorate at the same time, reminding us of a future that can only really happen in terms of a revolution in the way we read these landscapes and measure the impact of external, unpredictable and uncontrollable factors on them. unpredictable and uncontrollable.

Camilla Bevilacqua